Ursula K. Le Guin

Ursula Kroeber Le Guin (21 oktober, 1929 – 22 january, 2018) was een schrijfster en feminist uit de de Verenigde Staten. Ze werkte als schrijfster vooral in de fantasy- en sciencefictiongenres. In haar lange carrière schreef een aantal boekenreeksen, kinderboeken, korte verhalen en ook poëzie en essays. Haar eerste geschriften werden in de jaren 1960' gepubliceerd en gingen vaak over futuristische of alternatieve werelden waarbij politiek, het milieu, sekseverhoudingen, seksualiteit, religie en etnografie in ander perspectief werden geplaatst.[1]

Biografie

Ursula Kroeber werd in 1929 geboren in Berkeley, California (Verenigde Staten) waar zij ook opgroeide. Haar ouders waren antropoloog Alfred Kroeber en schrijfter Theodora Kroeber. Ze ging naar Radcliffe Collegge en studeerde uiteindelijk af aan Columbia University. Ze trouwde in 1953 met Charles A. Le Guin, een historicus uit Parijs. Sinds 1958 heeft zij vervolgens in Portland, Oregon (V.S.) gewoond, waar zij drie kinderen kreeg.[2]

Thematiek

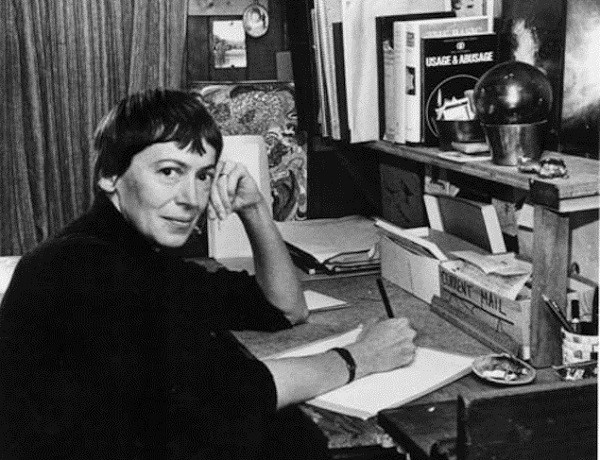

Ursula K. Le Guin tijdens de uitreiking van de medaille voor haar “onderscheidende bijdrage aan de Amerikaanse letterkunst” tijdens de 65ste National Book Awards, 19 november 2014.

Le Guin gebruikt de creatieve flexibiliteit van de sciencefiction- en fantasygenres als middel om sociale en psychologische identiteit en bredere culturele en sociale structuren te onderzoeken. Hierbij maakt ze gebruik van sociologie, antropologie en psychologie. Critici hebben haar werk hierom soms als ‘soft sciencefiction’ bestempeld.[3] Een term die zij verwerpt, omdat deze naar haar mening verdeeld en een nauw begrip hanteert van wat ‘valide’ sciencefiction is. Ook onderliggende ideeën als anarchisme en milieustrijd zijn terugkerende thema’s door het werk van Le Guin.

In 2014 zei Le Guin over overdenken van mogelijke toekomstbeelden in sciencefiction:

“[Over de toekomst] kan alles gezegd worden te gebeuren zonder de angst voor weerleggingen door een tijdsgenoot. De toekomst is een veilig, steriel laboratorium dat het mogelijk maakt ideeën uit te proberen, een middel om te denken over de realiteit, een methode.”[4]

Pshychologie, antropologie en gender

Being so thoroughly informed by social science perspectives on identity and society, Le Guin treats race and gender quite deliberately. The majority of her main characters are people of color, a choice made to reflect the non-white majority of humans, and one to which she attributes the frequent lack of character illustrations on her book covers.[36] Her writing often makes use of alien (i.e., human but non-Terran) cultures to examine structural characteristics of human culture and society and their impact on the individual. This prominent theme of cultural interaction is most likely rooted in the fact that Le Guin grew up in a household of anthropologists where she was surrounded by the remarkable case of Ishi – a Native American acclaimed in his time as the “last wild Indian” – and his interaction with the white man's world. Le Guin's father was director of the University of California Museum of Anthropology, where Ishi was studied and worked as a research assistant. Her mother wrote the bestseller Ishi in Two Worlds. Similar elements are echoed through many of Le Guin's stories – from Planet of Exile and City of Illusions to The Word for World Is Forest and The Dispossessed.[36]

Le Guin's writing notably employs the ordinary actions and transactions of everyday life, clarifying how these daily activities embed individuals in a context of relation to the physical world and to one another. For example, the engagement of the main characters with the everyday business of looking after animals, tending gardens and doing domestic chores is central to the novel Tehanu. Themes of Jungian psychology also are prominent in her writing.[37]

For example Le Guin's Hainish Cycle, a series of novels encompassing a loose collection of societies, of various related human species, that exist largely in isolation from one another, providing the setting for her explorations of intercultural encounter. The Left Hand of Darkness, The Dispossessed and The Telling all consider the consequences of contact between different worlds and cultures. Unlike those in much mainstream science fiction, Hainish Cycle civilization does not possess reliable human faster-than-light travel, but does have technology for instantaneous communication. The social and cultural impact of the arrival of Ekumen envoys (known as “mobiles”) on remote planets, and the culture shock that the envoys experience, constitute major themes of The Left Hand of Darkness. Le Guin's concept has been borrowed explicitly by several other well-known authors, to the extent of using the name of the communication device (the “ansible”).[38] The Left Hand of Darkness is particularly noted for the way she explores social, cultural, and personal consequences of sexual identity through a novel involving a human's encounter with an intermittently androgynous race.[39]

Milieu

Elizabeth McDowell states in her 1992 master's thesis that Le Guin “identif[ies] the present dominant socio-political American system as problematic and destructive to the health and life of the natural world, humanity, and their interrelations”.[40] This idea recurs in several of Le Guin's works, most notably The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), The Word for World Is Forest (1972), The Dispossessed (1974), The Eye of the Heron (1978), Always Coming Home (1985), and “Buffalo Gals, Won't You Come Out Tonight” (1987). All of these works center on ideas regarding socio-political organization and value-system experiments in both utopias and dystopias.[41] As McDowell explains, “Although many of Le Guin's works are exercises in the fantastic imagination, they are equally exercises of the political imagination.”[41]

In addition to her fiction, Le Guin's book Out Here: Poems and Images from Steens Mountain Country, a collaboration with artist Roger Dorband, is a clear environmental testament to the natural beauty of that area of Eastern Oregon.[citation needed]

Anarchisme en taoïsme

Le Guin's feelings towards anarchism were closely tied to her Taoist beliefs and both ideas appear in her work. “Taoism and Anarchism fit together in some very interesting ways and I've been a Taoist ever since I learned what it was.”[42] She participated in numerous peace marches and although she did not call herself an anarchist, since she did not live the lifestyle, she did feel that “Democracy is good but it isn't the only way to achieve justice and a fair share.”[43] Le Guin said: “The Dispossessed is an Anarchist utopian novel. Its ideas come from the Pacifist Anarchist tradition – Kropotkin etc. So did some of the ideas of the so-called counterculture of the sixties and seventies.”[44] She also said that anarchism “is a necessary ideal at the very least. It is an ideal without which we couldn't go on. If you are asking me is anarchism at this point a practical movement, well, then you get in the question of where you try to do it and who's living on your boundary?”[45]

Le Guin has been credited with helping to popularize anarchism as her work “rescues anarchism from the cultural ghetto to which it has been consigned [and] introduces the anarchist vision…into the mainstream of intellectual discourse”. Indeed her works were influential in developing a new anarchist way of thinking; a postmodern way that is more adaptable and looks at/addresses a broader range of concerns.[46]

Geselecteerd werk

Zie hier voor Ursula K. Le Guins volledige bibliografie.

Earthsea fantasy serie

- A Wizard of Earthsea, 1968 (genoemd in de lijst van de Lewis Carroll Shelf Award, 1979)

- The Tombs of Atuan, 1971 (Newbery Silver Medal Award)

- The Farthest Shore, 1972 (National Book Award)

- Tehanu: The Last Book of Earthsea, 1990 (Nebula Award; Locus Fantasy Award)

- Tales from Earthsea, 2001 (korte verhalen)

- The Other Wind, 2001 (World Fantasy Award, 2002)

Hainish science fiction serie

- Rocannon's World, 1966

- Planet of Exile, 1966

- City of Illusions, 1967

- The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969 (Hugo Award; Nebula Award)

- The Dispossessed, 1974 (Nebula Award; Hugo Award; Locus Award)

- The Word for World Is Forest, 1976 (Hugo Award, beste roman)

- Four Ways to Forgiveness, 1995 (Four Stories of the Ekumen)

- The Telling, 2000 (Locus SF Award; Endeavour Award)

Losse werken

- The Lathe of Heaven, 1971 (Locus SF Award)

- The Wind's Twelve Quarters, 1975

- Orsinian Tales, 1976

- The Eye of the Heron, 1978 (voor het eerste gepubliceerd in de bundel Millenial Women)

- The Beginning Place, 1980 (ook gepubliceerd als Threshold, 1986)

- The Compass Rose, 1982

- Always Coming Home, 1985

- Searoad: Chronicles of Klatsand, 1991

- The Birthday of the World: and Other Stories, 2002

- Annals of the Western Shore, 2004–2007 (Powers, het derde boek, won de Nebula Award voor beste roman)

- Lavinia, 2008 (Locus Fantasy Award)

Documentaire

Filmmaker Arwen Curry is in 2009 begonnen aan een documentaire over Le Guin. Curry filmde uren aan interviews met Le Guin, en tevens met vele schrijvers en artiesten die door haar werk werden geïnspireerd. In 2016 werd er een crowdfundingcampagne georganiseerd om de film af te kunnen maken. Halverwege 2017 zou deze film moeten zijn verschenen onder de titel Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin (Werelden van Ursula K. Le Guin).

Bronnen

- [3] Spivack, Charlotte (1984), Only in Dying, Life': The Dynamics of Old Age in the Fiction of Ursula Le Guin, Modern Language Studies, p.43–53.

- [4] Ursula K. Le Guin, (interview), Vice (vice.com)

- [5] Gunn, Eileen (May 2014), How America's Leading SF Authors Are Shaping Your Future, Smithsonian Magazine